LANDSCAPE PUNK 2: ROOTS GROWING

'The hills in our minds cannot be measured in miles’

Leatherface, ‘Shipyards’

‘I am a frontiersman, trapped in suburban England.’

Million Dead, ‘After the Rush Hour’

By 2001 I was at university in Norwich, studying English Literature at UEA. I was still a big punk fan, into the American hardcore bands of the 1980s (Black Flag, Minor Threat, Bad Brains etc.), and getting into the then-current wave of UK ska punk spearheaded by Household Name records and Capdown (whose first two albums remain indispensable records – and they were from Milton Keynes of all places). But that feeling I’d had listening to ‘Men an Tol’, those trips around the country bird-watching and looking at old ruins, had receded; the fact is that it simply wasn’t fashionable. I was unlikely to impress a girl talking about the Levellers, guillemots and the Saxon shoreway. And so, for a while, all those feelings and interest were forgotten about.

Around 2003, my then-girlfriend recommended I read a book called Kelly + Victor by the author Niall Griffiths. A raging, extreme and demotic novel set in Liverpool at the turn of the millennium, it set me on a different path. Studying literature at a grammar school, and then in the university system, I believed that what we called literature was a rarefied thing; or if not that, from faraway and exotic places like Paris or New York. The great British working class novels had been and gone, I thought – A Kestrel for a Knave and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner were from a remote past with no relevance, surely, to now. True literature seemed born from a class I was not a part of, from an unrecoverable past, or from countries and cities that exuded so much more charm and sex appeal than the dreary coastlines of Kent, the quiet and genteel streets of Norwich.

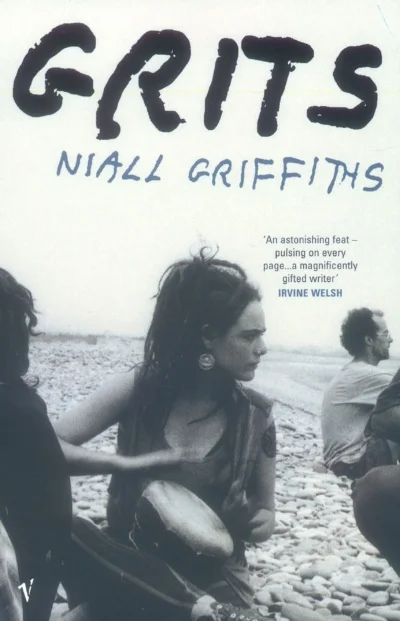

Reading Niall Griffiths changed all that. If Kelly + Victor had me hooked, then it was Grits (Griffiths’ debut) that knocked me for six. It’s a novel I return to again and again, and is one of the key literary keystones in my life. I’ve written a lot about Griffiths here and even had the pleasure of interviewing (and getting mightily drunk with) him in Aberystwyth, so there’s no need to repeat myself too much – but do go read those pieces if you want to know more.

What was important about reading Grits was that it completely changed how I saw what literature could be. This was contemporary but with a keen sense of not only history, but deep, geological time. This was writing about people from the margins, not the Hampstead middle classes or the university elites. More importantly it was not written by one of those people.

I’ve always believed people have pretty good bullshit-detectors, and can innately sense authenticity. This was authentic. This was writing about places I felt I understood; and that feeling I’d had at 12 years-old listening to ‘Men an Tol’ all came crashing back. The feeling of neck-hair prickling I’d had in certain landscapes, and got from my favourite, urgent, punk songs – I realised that writing could create the same feeling, and was innately connected to those things. It was all part of something reachable, if you knew how to look at the world in the right way. I wasn’t mad; other people felt this way. (This is what I want to achieve in my own work - to create that feeling and be a part of that tradition).

It’s hard to over-exaggerate how powerful that feeling can be, to realise you’re not alone (and remember this was in the pre-social media age, when it was that bit harder to find like-minded souls.)

I learned that it was possible to write about the very real effect of the British landscape on the individual. It was possible to write genuinely about people struggling with booze and substance addiction, members of Britain’s various sub-cultural tribes, about folk, rave and punk cultures, with anger, beauty and grace. Not only was it possible, but you could do it in the most gorgeous lyrical prose and vulgar demotic language at the same time. All of a sudden all those days spent trudging around Dover castle, being dive-bombed by terns on the Farne Islands, sleeping in my dad’s old camper van, listening to all that music that had been jettisoned for being naff and out of fashion, it was all worth it. It could be turned into something real and it did mean something. It could be literature.

From there, it would lead me to the better work of John King (Human Punk and Skinheads), the novels of Ron Berry (who wrote the incomparable So Long, Hector Bebb), Alexander Baron, Laura Oldfield Ford, JA Baker, Kathleen Jamie, Alan Garner, Roland Camberton, Dominic Cooper, Cynan Jones, Ben Myers, Arthur Machen and so many more. I was on the right path.

(Note: In a recent email exchange with Niall Griffiths, it turns out we share a love of Robert Aickman, Ramsey Campbell and Thomas Ligotti – the discussion about horror and weird fiction is for another post, but the sense that all the elements we want to include in landscape punk were connected, always, before we tried to give it a name, is very strong.)

Norwich, you may be surprised to hear, had a pretty good underground punk scene. I spent many weekends the Ferryboat Inn with my friend Paul Case (AKA performance poet Captain of the Rant), seeing all manner of bands ranging from the brilliant (Strike Anywhere, Million Dead, Leatherface) to the fucking terrible (names thankfully forgotten). This was my first real engagement, as an adult, with the British underground. Kent, sadly, didn’t have too much going on, and still doesn’t – though there were odd pockets. We’d head to Margate (way before its current makeover) up to the old Lido to see touring American punks, running back for the train past burly bouncers and prostitutes touting for business. It seems strange to recollect that now, seeing what Margate is becoming. But it did happen, and it’s important to remember the stuff that doesn’t make the official cut.

So about the time of discovering Niall Griffiths’ books, I was learning a hell of a lot more about the history of Britain’s underground scenes though those nights down at the Ferryboat. I’d start to hear the names of bands not from any American tradition – Crass, Conflict, the Subhumans. I was still unsure of what it all was, but my interest was piqued. Back then I was still in love with Jawbreaker, Husker Du and the like. But through my fandom of the US group Hot Water Music, I first listened to the Sunderland band, Leatherface (Hot Water Music had covered a track of theirs, ‘Springtime’.) This was another revelatory moment – a British punk band with erudite, poetic lyrics, cryptic meanings and a world-weary bar room philosopher stance more akin to Leonard Cohen than the Pistols. I didn’t know the term back then, but I can think of at least two Leatherface songs that fit into what we’d call psychogeography – the fantastic ‘Dead Industrial Atmosphere’ with its air ‘that smells of religion’ and the piano and drums oddity ‘Shipyards’ which contains the line:

The hills in our minds cannot be measured in miles.

It’s a line that’s stuck with me through the years. It resonated then, and it continues to resonate now as I write this. It proved to me that my interest in place and literature, and subculture, were not separate things.

When I ended up in a huge shared house in Stoke Newington, a decade ago, all this stuff was sloshing around in my head without any true coherence. I had the feeling but not the words to express it.

Moving to London was when I truly found what I mean when I use the word ‘punk’. It was where I read my first Iain Sinclair book, and was introduced to a concept and methodology that fitted all those powerful feelings elicited in me by landscape, by music and by literature. In London was where I’d start to run DIY punk and poetry nights with Paul Case and meet a whole raft of like-minded people I still count as friends to this day. It’s where I encountered real protest culture, the shady world of squatting, and the sheer oddness of the city; I can still recall the first time I simply went for a walk from my house in N16 and ended up at the Middlesex Filter Beds on the Lee Navigation. Something that, I’m sure, ended up with Influx Press publishing Gareth E. Rees’ Marshland. London gave me the balls to take those realisations given to me by Grits and start to act on it. I have a lot to thank the city for.

It was also around this time that I began reading the Hellblazer comics by Jamie Delano, read Shibboleth by Penny Rimbaud, discovered the Inner Terrestrials, and helped run a squat gig that is still spoken about in notorious terms to this day.

More on this next time.