I can see where it began to unravel. That summer; the one the whole country remembers. I was twenty-five-years-old, the tarmac of London oozing in the heat. Hotter than Spain, screamed the headlines. Much flesh on display.

The city was burning. Five night of riots, triggered by something so common we’d almost all forgotten it was a travesty. The police choked a young black lad squeezed the life out of him, as they’d done to so many before. It was out Wood Green way.

PK and I had taken our fair share of batterings out on the demos, and Andy once took a beating in the cells of Stoke Newington for having too much of a mouth on him. But we considered ourselves lucky – we put ourselves in those situations. I see that now. The police didn’t come looking for us.

For whatever reason, people weren’t having it that summer. Who can blame them. Push people too far, then punish them for having the gall to react – the sheer nerve of it. The put-upon of London reacted with torched squad cars, bricks through the windows of Currys, looting all those things they were told they needed to be a proper person, but could not afford.

Petrol bombs burst on riot shields, a gorgeous, compelling and frightening sight. The memories of London streets lit at night by oily flame, so beautiful. Rip it up, tear it down, smash, start again. If only it had been that way.

Even back then I knew the violence, the unhappiness and unrest, was nothing new to London. This ancient city, my home, a place I knew like one of its rats, eking life out in the cracks and gaps. I had this… what’d you call a gift. A gift that isolated me.

I could see the ghosts of the all the cities London had been. I’d often catch glimpses of men and women in outdated clothing, and wonder. It was so hard to tell who was living and who was dead – with retro fashion booming, second-hand chic a thing, even skinhead fashion suffering a fashionable re-appreciation, how could I tell when anyone was from? And who was I, anyway, to pass judgment on this? Whether I was decked out, like I was back then, in the black and white t-shirts of bands from the early eighties, or smartened up in polo shirts, when the hell was I from? I burned with nostalgia for times that never really happened.

The weight of the city I lived in crushed me. I couldn’t verbalise it. It was a drug. I’d sit and watch old Pogues videos, flick through my shelves of London fiction, stare out high as a kite over the view from London Bridge at five am as the sun came up, and the knowledge of where I was, what this city was and the fact that I lived in it – I lived in it – became unbearable. Like a pill you’d taken that you knew was too strong, with the rush of emotions feeling enough to buckle me at the spine. I never knew what to call those feelings. Some kind of extra, unnecessary, sensitivity.

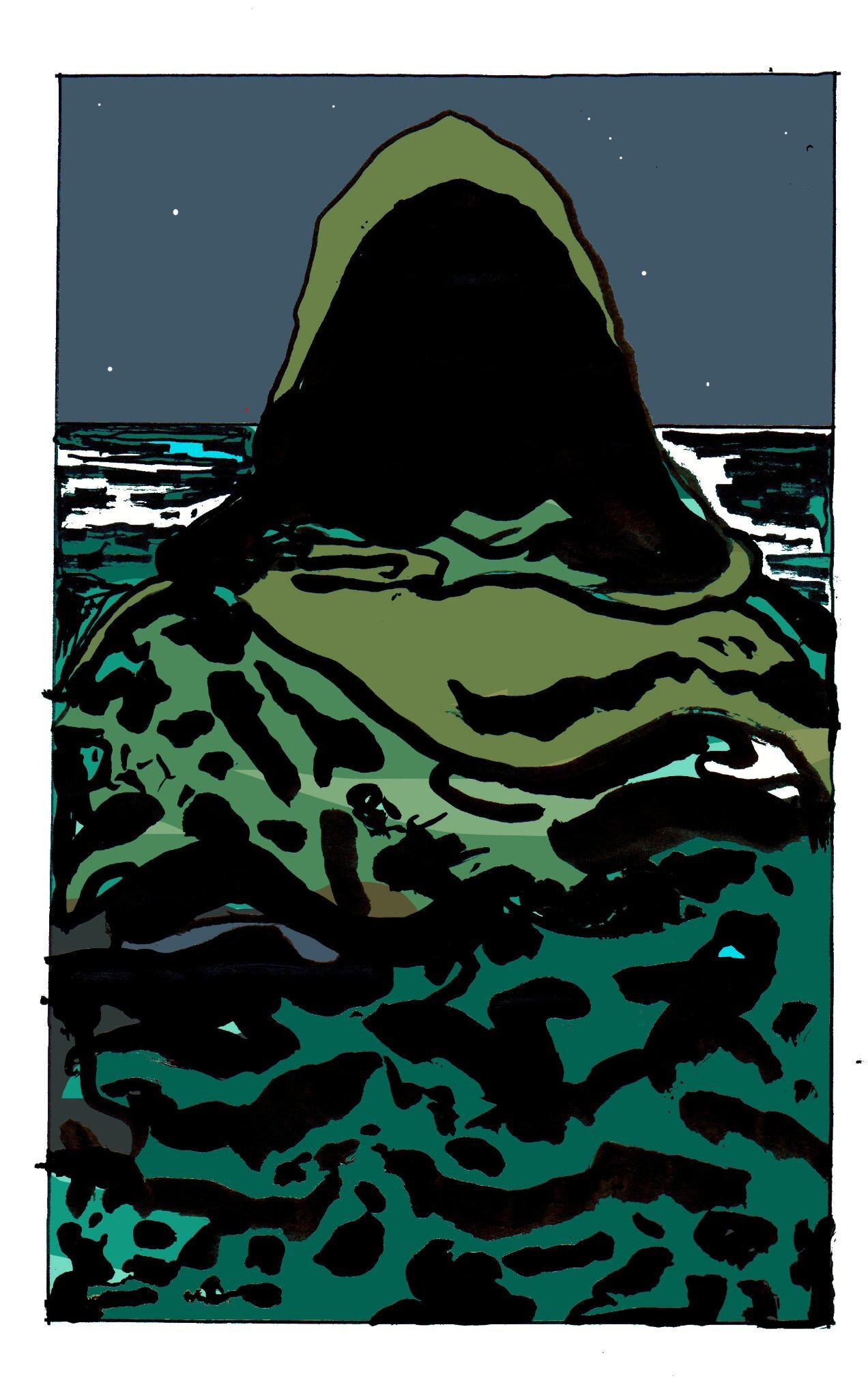

I saw the spriggan on Parkland Walk struggling to get free of the brickwork when no one else could; I knew the golem in Stamford Hill was real. I studied the tarot, I loved weird fiction, and took an interest in things like the collective unconscious. I had taken mushrooms, acid, even DMT down on the south coast in Hastings, an experience which almost made me believe in an afterlife.

That night as the city burned, we thought we’d nose out what was going on, try and live up to some of the creeds we claimed to adhere to. I can still see Jess, in her light denim jacket with covered in patches promoting causes that mattered in those days, plain black T shirt, hair shaved along one side of the head like the girls used to do back then. It was before we really got together, and way before it all turned to shit.

We were running down a side road off the Green Lanes, fleeing it as a whole unit of riot police done up like a dystopian enforcers marched down the street. Turks and kurds leaning out of their windows above the kebab shops and grocery stores. I have a memory of a tipped-over box of Turkish peppers, those pale green ones your cook up with eggs in a metal pan, arranged like an absurd, crushed corona on the tarmac

Some of the Turks were out on the street, tooled up with cleavers and bats that should have been hitting softballs in London’s parks. They were a community that knew how to look after themselves, and I always respected them for that. They were defending their property from the looters, people we presumed they knew as neighbours.

We ran down the alley as the Green Lanes went up in flames and came down in smashed glass and scorched brick. Jess and I had lost the others, and it felt like we were in theold Alex Cox movie, Sid & Nancy, excited and adrenalised by the fact that things were happening and for once the status quo was wobbling. We kissed in the shadow behind a green industrial recycling bin, a piece of smouldering cardboard wafting above us like a burning angel.